It is not unusual to overhear students comparing schedules the way athletes compare stats. One person mentions staying up past midnight to finish an assignment, another responds with a heavier workload, and the exchange ends with a shared understanding that exhaustion is evidence of seriousness. In this environment, being busy is rarely treated as a problem to solve. More often, it is taken as proof that things are going according to plan.

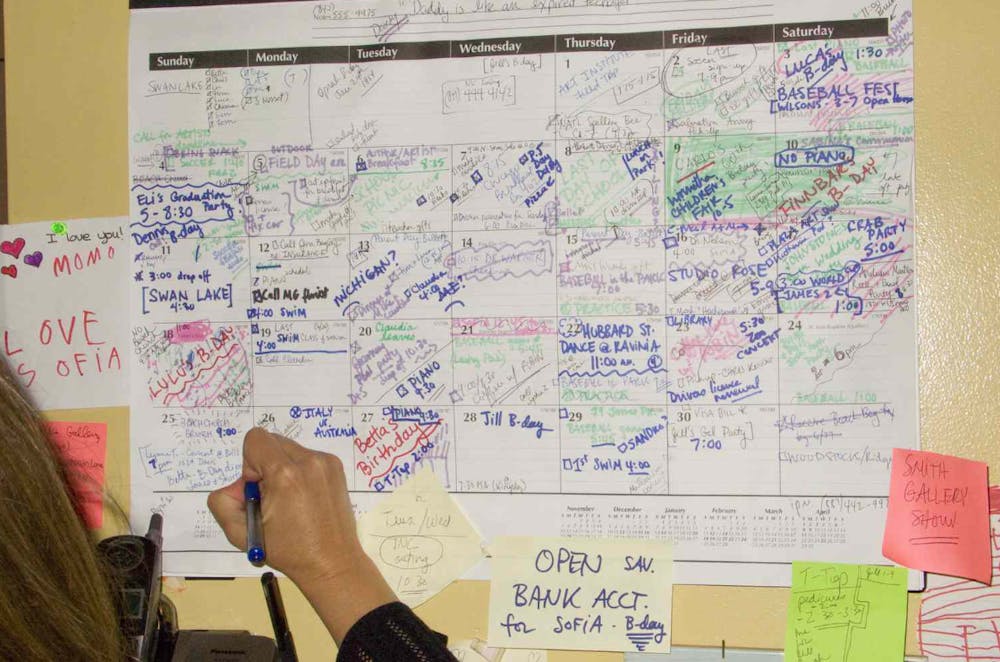

Schools encourage and create this interpretation. Progress is tracked through visible outputs: grades posted online, assignments submitted, hours logged, roles held. Productivity fits neatly into these systems because it produces measurable results. A completed problem set, a finished essay, a checked box on a planner all provide immediate and highly tangible confirmation that time was used “correctly.” Over time, students learn to organize their days around these signals, filling gaps with tasks and measuring success by how much ground they cover. We have become used to the idea that "productivity," a word that literally means our ability to create output, is something to covet.

The appeal of productivity lies in its clarity. When work is broken into discrete units, effort feels justified. Even when the work is tedious, there is comfort in knowing what must be done next. This structure becomes especially attractive in an academic environment that is competitive and future-oriented. Staying busy offers a sense of momentum, a way to feel prepared for what comes next. Idleness, by contrast, feels risky. There’s an idea that in college you should always do some form of work every day, no matter what. This is out of fear of running out of momentum and reaching some theoretical stagnation. Even if this advice is well-intentioned, it reinforces the idea that productivity must be continuous, and that stepping away from work, even once, will carry an implicit cost.

Yet this constant motion has side effects. Many students are familiar with the experience of finishing a long stretch of work only to feel oddly unchanged by it. Hours disappear into assignments that are completed and quickly forgotten. It would be easy to say that a day feels full, but what’s more difficult is achieving substantivity. Activities that require sustained attention without a clear endpoint like reading for pleasure, thinking through an idea, talking without an agenda, are often postponed or quietly abandoned. They do not fit easily into productivity frameworks, and so they are treated as optional. There's an irony in how schools disparage cellphones and other forms of instant gratification, only to praise similar behavior if it applies to learning. This effect gives off the feeling of a conditioning process, rather than an inspiring education.

This is where fulfillment begins to diverge from productivity. Fulfillment tends to emerge from depth rather than volume. It is tied to engagement, interest, and a sense that attention is being used deliberately. These experiences are harder to quantify and even harder to profit off of. They do not always produce immediate outcomes, and they resist being optimized. It’s kind of like hand-made knitted sweaters trying to compete with mass-produced polyester shirts. Sure, there are those that would choose the former, but those same people would generally be less concerned with money. As a result, these intangibles are easier to deprioritize, especially when schedules are already crowded.

This does not mean that discipline or structure should be discarded. Productivity serves a purpose, particularly in environments with real demands and deadlines. But when hardworking people derive a second-hand fulfillment from the badge of honor that productivity has provided, I think the values we encourage in education need to be reevaluated.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

As students move through increasingly optimized routines, the distinction between staying busy and staying engaged becomes more important. Productivity can fill a day, but fulfillment determines whether that day feels lived. Recognizing the difference requires paying attention to what remains once the work is done, and whether the effort points toward something that lasts beyond the checklist.