The core concept of democracy is that all voters have an equal voice; in a democratic republic like the United States, voters use that voice to elect the politicians they want to represent them. But this system loses legitimacy when not all voters get to have an equal impact.

Gerrymandering, or partisan redistricting, which occurs once every decade, is a process that manipulates district lines favoring certain parties. Under this process, politicians are able to analyze the area they aim to serve and draw lines to figure out which voters they want in their district and which ones they don’t. This rigs the voting system by eliminating competition between parties and giving certain candidates advantages in individual districts. Instead of defining voting districts by looking at how election maps represent communities on state and national levels, it is focused on guaranteeing that parties can win elections with less actual voter support.

Former election map drawer and Republican political strategist Thomas Hofeller once stated, “Redistricting is like an election in reverse! ...Usually, voters get to pick the politicians. In redistricting politicians get to pick the voters!”

Redistricting leads to significant partisan biases in maps. For example, in 2018, Democrats in Wisconsin won every statewide office and a majority of the statewide vote, but due to gerrymandering won only 36 of the 99 seats in the state assembly. Gerrymandering most affects the public and the voters; rigged maps make elections less competitive, and in turn, make Americans feel like their votes don’t matter.

There are two main forms of gerrymandering. The first is packing, where politicians try to cram as many of the opposition’s voters as possible into a single district. The goal of packing is to limit how many seats the opposition control. The second form, cracking, is the opposite strategy. In cracking, politicians divide the opposing party's voters across many districts to prevent them from being in the majority in any of them.

It is important to note that both parties are guilty of gerrymandering while also successfully litigating against it. However, the Republican Party has gained the greatest advantage from this process. In states where partisan legislatures draw district lines, Republicans hold 20 states with 187 districts while Democrats hold eight states with 75 districts.

Republican control over gerrymandering increased in 2010 with a political strategy called Project Red Map. Based on the idea that “He who controls redistricting controls congress”, this strategy targeted states where just a few state House seats could shift the balance to Republican control.

It worked incredibly well and continues to help Republicans gain majorities in districts today, and explains how in 2012, Democratic state House candidates won 51 percent of the vote in Pennsylvania, yet ended up with only 28 percent of the seats in the House of Representatives. Project Red Map gave Republicans a lasting lead for the 2010 decade. Over the 2012, 2014, and 2016 midterm elections, gerrymandering shifted 59 congressional seats, 39 for Republicans and 20 for Democrats.

2020 was a very important year, as both an election and redistricting year. Just one year prior, the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts can not do anything to stop extreme gerrymandering on partisan grounds. As a result, partisan gerrymandering surged in 2020. In Oregon, Democrats redrew the state’s map so all but one of its six districts leaned their way, as well as trying to crack three seats out of Illinois.

Republicans took an ambitious approach in Ohio, proposing one map that could leave Democrats with just two seats out of 15 in a state where Trump won by a slight margin of 8 percent. The 2020 redistricting census controlled by Republicans is having its effects seen in the most recent 2022 midterm election. Although the midterm was not the expected red wave, the new lines formed from redistricting helped Republicans take control of the House.

As of 2019, there are no current laws explicitly preventing gerrymandering, but there are a few limits in place. Each district must have roughly the same number of people and often have to be compact. Lawmakers also can not dilute voter influence based on race, and using maps to diminish the power of specific racial or ethnic groups is illegal. Although these are the laws, recent controversy surrounding them has led to both parties being sued in select states.

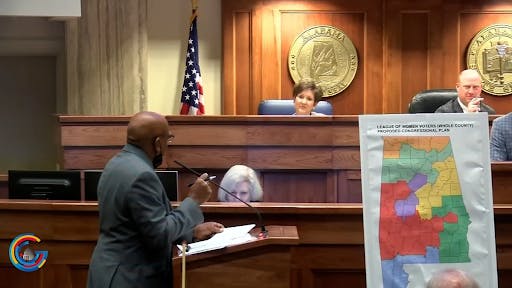

Supreme Court taking Alabama gerrymandering case | Courtesy: DC Bureau

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

A major lawsuit taking place in Alabama was eventually brought to the Supreme Court. The case, Merril v. Milligan, accused Republican lawmakers of packing and cracking Alabama’s districts to ensure that Black voters represented 56% of one district but no more than 30% in any other. Despite representing 28% of the state population, Black Alabamans could only expect to influence elections in the 7th district, a severe violation of the Voting Rights Act. In February, the Supreme Court ordered Alabama to redraw its voter maps, however, the contested map remained influential in the 2022 midterms.

In North Carolina, the Supreme Court rejected the district maps drawn up by Republicans, deeming them overly partisan and ordering them redrawn. This led to partisan gerrymandering reentering the Supreme Court and the looming question of whether state courts may rule that redistricting violates the state constitution. Justices ruled to allow states action in their constitution if believed to be politically rigged. The rulings also found that Republicans acted unconstitutionally to diminish the influence of Democrat voters by both passing voter ID laws (in which one must show proof of identification to vote) and redrawing the maps rendering many Democrat votes unimpactful.

In 2014, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo passed an amendment that changed the way the state’s political maps were drawn, boasting that this would permanently reform New York’s redistricting process. However, this wasn’t the case, and the changes led to the process being more open to political manipulation. The reforms state that a map drawer must consider communities of interest but do not provide any details on how to do so nor define what constitutes a community of interest.

In the May 2022 primary, New York redistricting was chaotic, with maps being thrown out and redrawn constantly. In the end, their maps are among the most competitive and politically balanced in the nation. But the treatment of some communities, especially in New York City, left many voters dissatisfied.

Gerrymandering is a threat to democracy in the United States. By favoring select political parties and racial groups, elections become less competitive and minority communities are perpetually disadvantaged. This leads to many Americans feeling like their voices don't matter. Nick Seabrook, a political scientist at the University of Florida states, “Redistricting creates an electoral system where the people in office are not representative of popular will. They are instead representing whomever is in charge of redistricting.”

The need for Congress to pass effective reforms is more urgent than ever. If gerrymandering is still allowed by the next redistricting year, we risk another decade of racially and politically discriminatory line drawing. Congress needs to act quickly — fair representation depends on it.

Chinese Translation Here